Many people when they get to a certain age start to wonder where they came from. That was certainly true for me so a few years ago I started to research my family tree. Although there were a few surprises my research confirmed that I my family were ordinary workers. I wanted to find out about my roots, about my ancestors, where they came from and how they lived. And as an occupational hygienist I couldn’t help but be interested in what they did for a living and their working conditions.

Coming from Lancashire it wasn’t a surprise to find that many of my ancestors who lived in the 19th and 20th Centuries were employed at some time during their lives in cotton mills. And working in cotton mills they were faced with a whole host of health risks.

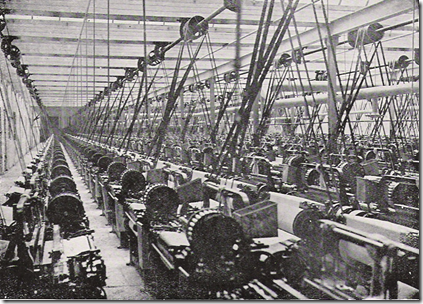

I’ve always been interested in industry and when I was a boy my mother arranged for me to have a look round the mill where she worked. The first thing that hit me when I walked in the mill was the tremendous noise. Levels in weaving sheds were likely to be well above 90 dBA – often approaching, or even exceeding 100 dB(A). Communication was difficult and mill workers soon learned how to lip read and communicating with each other by “mee mawing” – a combination of exaggerated lip movements and miming

Not surprisingly many cotton workers developed noise induced hearing loss – one study in 1927 suggested that at least 27% of cotton workers in Lancashire suffered some degree of deafness. Personally, I think that’s an underestimation. This is how the term “cloth ears” entered the language – it was well known that workers in the mills were hard of hearing.

This lady is a weaver and is kissing the shuttle – sucking the thread through to load the shuttle ready for weaving.

This practice presented a number of health risks – the transmission of infectious diseases, such as TB, but as the shuttle would be contaminated with oil, and the oils used then were unrefined mineral oil – there was a risk of developing cancer of the mouth.

Exposure to oil occurred in other ways particularly for workers who had direct contact with machinery or where splashing of oil could occur. There was a high incidence of scrotal cancer in men who operated mule spinners – and this was a problem even in the 1920s. In earlier times workers in mills had to work in bare feet as the irons on their clogs could create sparks which could initiate a fire due to the floorboards being soaked with oil. Contact with these very oil soaked floorboards led to cases of foot cancer.

And of course there was the dust. Exposure to cotton dust, particularly during early stages of production, can lead to the development of byssinosis – a debilitating respiratory disease. An allergic condition, it was often known as “Monday fever” as symptoms were worst on Mondays, easing off during the week. A study on 1909 reported that around 75% of mill workers suffered from respiratory disease.

The worst areas for dust exposures were the carding rooms where the cotton was prepared ready for spinning, but dust levels could be high in spinning rooms too.

Although control measures started to be introduced in the 1920’s workers continued to be exposed to dust levels that could cause byssinosis. Studies in the 1950’s showed than more than 60% of card room workers developed the disease as well as around 10 to 20% of workers in some spinning rooms.

A lot of work was devoted to studying dust levels, developing standards and control measures by the early pioneers of occupational hygiene in the UK and I’m sure this contributed to improved conditions in the cotton industry in the UK. I’m not sure I’d like to have to operate their dust sampling kit though – it certainly wasn’t personal sampling!

Today things are different. The carding machines, spinning frames and looms are silent and have been sent for scrap. The mills have been abandoned and are derelict or demolished or have been converted for other uses.

Cotton is still in demand but it’s a competitive market and the work has been moved to other countries where labour is cheap and standards are not as high – Africa, China and the Indian sub-continent. Another consequence of globalisation. Although you could say that the industry is returning to where it originated in the days before the industrial revolution. Sadly, conditions and working methods in many workplaces in the developing world are primitive and controls are minimal. It seems like the lessons learned in the 20th Century in the traditional economies are rarely applied so not surprisingly those traditional diseases associated with the industry are re-emerging in developing economies.

Studies carried out in recent years have shown high incidences of byssinosis in some mills developing countries. One study in Karachi, Pakistan in 2008 found that among 362 textile workers 35.6% had byssinosis. (Prevalence of Byssinosis in Spinning and Textile Workers of Karachi, Pakistan, Archives of Environmental & Occupational Health, Vol. 63, No. 3, 2008 ). A study of textile workers in Ethiopia published in 2010 showed a similar proportion – 38% had developed byssinosis, with 84.6% of workers in the carding section suffering from the disease

Another study, this time into textile workers’ noise exposures in Pakistan indicated noise levels in the range 88.4-104 dB(A). 57% were unaware that noise caused hearing damage and almost 50% didn’t wear ear defenders

William Blake wrote of “Dark Satanic Mills” in 1804. This was still a fair description of the working conditions in Lancashire when my ancestors worked in the mills. And I believe its valid today in many workplaces in the developing world.

It’s not easy to get accurate figures on occupational health in the UK and so much more difficult in the developing world. The best estimate we have (and it’s likely to be an underestimate) is that 2.3 million people die due to accidents at work and work related disease (World health Organisation). And the vast majority of these are due to ill health

Some occupational hygienists might take a dispassionate, academic interests in dust exposure. But I think most of us are motivated by a genuine desire to prevent ill health at work and improve working conditions. Many of us work in countries where conditions although far from perfect are relatively good. But can we turn a blind eye to what’s happening in the rest of the world?

Personally, I think it’s something we need to be thinking about.

Hello, I admire your taking on this subject. I’m a U.S. based occupational therapist and also write poetry. I’m working on a collection of poems narrating the rise of the textile mills in the Pawtucket, Rhode Island region—and the consequences of industrialization, notably, the TB epidemic. I’d like to know if you could share a source for the photo in your article of the female weaver ” kissing” the shuttle? I’d like to include it, if possible, in my collection. Thanks for your article and for any information you can provide about this photo.

Best regards,

Mary Ann Mayer

Hi Mary

I’m afraid I can’t remember where I obtained this picture from. These days I usually try to credit the source of pictures I use, but I neglected to do so. Sorry!

Found the picture at http://www.cottontown.org/howweusedtolive/Down%20Memory%20Lane/Pages/Hundred-Years-Ago.aspx though I’m afraid I have no idea if it was in the original article from 1912 or not (“SHUTTLE KISSING REPORT EVILS NOT SO SERIOUS”, partway through the page). I toured part of the “Museum of Science and Industry” in Manchester UK yesterday (Sept. 8, 2017) and they have working editions of several models of looms and other machines. To our small and informal group the guide rather discreetly pointed out the difference between a kissing shuttle and its replacement, the latter having been patented and manufactured soon after any dangers of the kissing shuttle were reported. The guide went on to state that plant owners would only replace shuttles when they broke or wore out – the industry was very competitive and cost savings were far more important than worker safety.

Hi Mary Ann, My company was a textile supply business and I called on many of the textile mills in NE, especially woolen mills. This was 1985 to present, Including the mills around Pawtucket. I would be interested in your book of poems.

Sincerely,

David Harris

JOEL S. Perkins & Son

Textile Mill Supplies Since 1880

Jsperk@sover.net

My dad worked for many years in a woolen mill here in Ashland NH. He never smoked, never drank and lived on a healthy holistic diet. He was also a Chiropractor so he used holistic healing all his life. However, in 2015 he suddenly developed lung cancer and was dead within a couple of months of being diagnosed! We have no clue where it came from. Is it possible he was exposed at the woolen mill? He worked in Carding and Weaving most of the time. The cancer struck so fast he didn’t even have time to fight back before it spread. He didn’t deserve that kind of death, no one does. Any help is appreciated. God bless.

Hi Melody. Sorry to hear about your father. It isn’t pleasant when a loved one suffers from such an awful disease.

There is certainly some evidence of lung cancer in textile workers. Usually not so much associated with exposure to the fibres themselves, but other agents that present during the process. See https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4986180/